At first sight you want to rejoice: six Aboriginal people in a parliament of 25 members, including one who campaigned on a treaty with the vastly dominant Australian white population and on Aboriginal sovereignty. But a reality check will soon show you the number won’t matter much in the way power works in the Northern Territory. A celebrity case in the thinly populated Territory’s August 28 election was the winning of the predominantly white and tiny bauxite mining town of Nhulunbuy by Aboriginal elder, Yingiya Mark Guyula, standing as an Independent. He won the usually seemingly unassailable Labor seat by a majority of eight votes (1,648 to 1,640) from a woman tapped to be the deputy chief minister in the Labor government that routed conservatives out of office (they’re left with two seats). Lynne Walker had held the seat since 2008, her Labor party since 1980.

Two days after Guyula had delivered his maiden speech to the house, his right to sit there was challenged on the flimsiest of grounds.

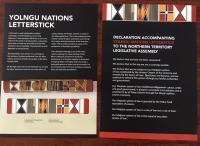

At the end of the speech, on behalf of the Yolngu Nations Assembly, which supported his election campaign, he tabled a letter which he said was a declaration of ongoing sovereignty and an invitation to work towards the mutual acceptance of Yolngu and Australian law.

Northern Territory law prevents someone who holds a public office from running in an election. The responsible electoral commission was told that Guyala was a member of a local government organisation, and took the case to a ‘court of disputed returns’. Guyala strenuously denied any such membership and a few days ago the court found in his favour.

So why challenge him like this in the first place? A long-time Aboriginal activist, Ghillar Michael Anderson, told me because “he stood on the tickets sovereignty and treaty now”.

What about the five other Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory parliament, who are all in the now governing Labor party? They are Ken Vowles, Ngaree Ah Kit, Lawrence Costa, Chansey Paech and Selena Uibo.

From profiles published by the National Indigenous Television:

Ken Vowles: The only Aboriginal cabinet minister, with the Chief Minister there are seven. Returned in the seat of Johnston. Among the Territory’s most famous cricketers, having travelled the world playing the sport. Born and raised in the Northern Territory. Now the Minister for Primary Industry and Resources, while in Opposition previously Spokesman for Indigenous Policy.

Ngaree Ah Kit: 34-year-old Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander candidate holding the seat of Karama. She says she is passionate about suicide prevention, and in 2010 helped establish the Darwin Region Indigenous Suicide Prevention Network. She has a family history of politics, with her father serving in government as the member for Arnhem from 1995-2005.

Lawrence Costa: Lives on his outstation Pitjarmirra just north of Melville Island, holds the seat of Arafura. Experienced in a variety of council roles and more than 20 years’ working in remote Aboriginal communities. He has Tiwi heritage.

Chansey Paech: Won the seat of Namatjira and is proud of his Indigenous heritage, with links to the Eastern Arrernte and Gurindji people. Has been a member of Territory Labor since he was a teenager. In 2012 he was elected to the Alice Springs Town Council. He says he enjoys the arts, gardening and horse riding.

Selena Uibo: Won the seat of Arnhem. Her Indigenous heritage links her to the Nunggubuyu and Wanandilyakwa people of south-east Arnhem Land. Uibo studied in education at the University of Queensland before moving back to the Territory to work at Casuarina Senior College. In 2012 she moved to work in her mother’s community of Numbulwar, where she is now the acting senior teacher at the local school.

Altogether 14 Aboriginal people stood for election.

A recap of who’s in the parliament: The government, led by Chief Minister Michael Gunner, with an overwhelming 18 seats out of 25; two Members of the Country Liberal Party (the conservatives just routed from government); five Independents.

Which brings me to the reality check mentioned in my opening paragraph. Although Aboriginal people make up a third of the Northern Territory’s population of 244,000 (2016, the highest proportion of any state or territory) and on paper own some 49% of the land and about 85% of its coastline, they have had very little clout in lawmaking or deciding what happens on their estate.

Whatever party ruled let them down badly. Usually to pamper miners. Mining dominates the Northern Territory economy. The maltreatment is too much to go into this report, so I recommend http://www.concernedaustralians.com.au/ for the background.

To move anything through the house Yingiya Mark Guyula will need allies.

Will he find them in the other five Aborigines on the government benches, or will those toe the Labor line?

Will he find support from the white Labor Members?

Will he win over the four other Independents?

Robyn Jane Lambley, a former minister in a previous conservative government;

Terence (Terry) Kennedy Mills, a former chief minister (conservative),

Kezia Dorcas Tibisay Purick, who prior to entering parliament was the CEO of the Northern Territory Minerals Council, the mining lobby, for 16 years;

and Gerard (Gerry) Vincent Wood, a former mayor and vegetable and poultry farmer.

Lots of ifs…

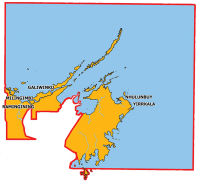

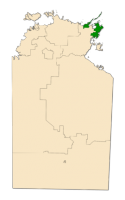

The seat of Nhulunbuy covers the north-eastern tip of Arnhem Land, taking in the mining town of Nhulunbuy itself as well as the Aboriginal communities Galiwinku, Yirrkala, Milingimbi, Ramingining and their outstations. A 2015 redistribution put Milingimbi and Ramingining from the division of Arnhem into Nhulunbuy, which raised Guyula’s electoral chances.

I have not been to Nhulunbuy, nor do I know anyone who has, but what I read on the Internet makes me comment cautiously that it is not a happy place. Racial divisions and tensions are said to be hard to ignore there.

In one of his earliest speeches in parliament, Guyula went into what is probably the most fraught issue, including between Aboriginal groups: land.

He criticised the Northern Land Council, one of the most powerful bodies in the Northern Territory, for the way it deals with land disputes. If you speculate between the lines he’s calling out corruption and nepotism. Read the full speech here (scroll down to Gove Peninsula Land Ownership).

“On a practice level for some years now it has been clear that the government entity established to advocate for our will, the Northern Land Council, is not following its obligations to land rights law. For example, the NLC fails to follow Madayin law when it does not acknowledge the Ngärrá institution as a political entity. Instead, the NLC says Ngärrá is just religious. Instead, it pretends that leadership is somehow otherwise empowered, but cannot explain how. One can imagine the chaos that ensues. Who, for example, makes a meeting authoritative?

“More, the NLC does not consider Ringitj-alliances in their consideration of land ownership. The NLC operates with a lazy approach to traditional Aboriginal ownership, working only with Bapurru clans, and they make their own law entirely, when they subdivide ownership into sub-clans.”

Located 650km east of Darwin,the Northern Territory capital, Nhulunbuy was set up purely to serve the giant Rio Tinto mining company’s bauxite mining and alumina smelting operation, originally against opposition from the Yolngu clans. The smelter was closed down in 2014, with the loss of 1,000 jobs, locals now fearing the mine could also close down. It is situated on what the company describes as extensive deposits of high grade bauxite, a burnished red ore with high aluminium oxide content.

“Everything here is hooked up for Rio Tinto: the power, water, everything,” says a resident who has lived in the town for several decades. He fears the change to come. “If the Yolngu people come in, it will change things a lot around here. It’s 99% white at the moment … we’ll see the crime rate go through the roof, it’ll be like Alice Springs or Tennant Creek here.”

When Rio Tinto closed the refinery Nhulunbuy’s population of 4,000 was halved, businesses closed, air links were cancelled and residents’ health suffered. Now they are trying to turn things around.

Houses still sit empty in Gove, the white name for the town, and there are calls for the government and Rio Tinto to make the dwellings available for public housing. The waiting list in Nhulunbuy is more than 12 years – the longest in the Territory.

“It’s very difficult to explain to people – particularly my Yolgnu constituents – who come to me about public housing and say why can’t I have one of these empty houses?” says former MP for the seat, Lynne Walker.

Practically no Indigenous people worked at the Gove refinery, yet the Yolngu people have been on the receiving end of the benefits – infrastructure, and payments to the two main clan groups – and the ignominies – the alcohol dependency, the suicide – that have come with the mine, both directly and indirectly.

The Yolngu didn’t want alcohol to be on sale in Nhulunbuy, but it is. Now parts of the beach at nearby Yirrkala, a Yolngu-dominated township where alcohol is banned, have a shimmering blanket of used Victoria Bitter cans.

More than 54% of Territorians, 78,925, live in the port city of Darwin, located in the territory's north, what locals call the Top End. Less than half of the territory's population live in rural areas.

To the detriment of small settlements (fewer votes are available there!) Governments of both stripes have consistently spent most on the larger towns Darwin (71,347 population), Alice Springs (24,640), Palmerston (20,570), Katherine (6,719), McMinns Lagoon (5,245), Nhulunbuy (3,804), Howard Springs (3,440), Tennant Creek (3,286), Yulara (2,527) and Jabiru (1,775).

The Northern Territory has Australia’s lowest level of voter registration, more than 33,000 Territorians “missing” from the electoral roll. Local political scientist, Professor Rolf Gerritsen, says the comparatively high indigenous population accounts for some of the missing voters.

“The Aboriginal population is increasingly disengaged from whitefella society and government and electoral politics,” he says. “A lot of Aboriginal people are just not interested in enrolling or they lose their enrolment because they move around so much.”

Voting is compulsory in Australia and not to do so can incur a fine. I thoroughly doubt, though, that ‘show cause’ letters will be going out to the farflung Aboriginal defaulters. I suspect politicians are only too glad that they don’t express their rage at the ballot box.

The transient nature of the non-indigenous population is also a factor. “We have a population that’s highly transitory. Between one election and the next, half the population has moved out of the NT. They’ve got other things on their minds; buying a dustpan and brush from Kmart or moving their kids’ school.”

Conservative voters are more likely to ensure their enrolment details are up to date, Gerritsen notes.

More than 100 Aboriginal languages are spoken in the Northern Territory, Australia’s most sparsely populated state or territory.

Recently here on Indymedia

Barrier-Reef-trashing monster coal mine to get a billion dollar tax handout

Ongoing crimes against humanity, gross violations of human rights, genocide, ethnocide, ecocide and persecution across ‘Australia’

New Australian 'biodiversity' law 'a direct assault on Aboriginal laws, culture, religion and spirituality'

Is South Australia’s nuclear dumping plan dead?

Report calls for change in Indigenous suicide prevention in Australia

Queenslanders can’t challenge giant coalmine’s dangerous water grab

Possible ‘first encounter’ Aboriginal shield uncovered in Berlin museum

Aboriginal children in care 'isolated from family and culture', says Victoria report

Growing up with family and culture is a human right. It's also essential for healing

Citizens jury trashes plan to absorb the world's nuclear waste in South Australia

Aborigines demand their historic shield and spears back from British museums

First contact was shooting an Aborigine protecting his country against invaders.

'Wholly void' election of Aboriginal member a 'landmark case'

Why a Treaty is Vital

Ecumenical Forum supports Treaty, Sovereignty and Constitutional Recognition

Opening discussion on Aboriginal Sovereignty and the Treaty process