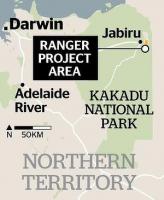

The skies above Jabiru are busy. Birds of prey circle endlessly. Brown falcons or whistling kites are a constant presence above this part of Kakadu National Park.

It creates a fitting mood for a place facing an uncertain future. Jabiru is a town in limbo. Four decades after arriving, uranium miner Energy Resources of Australia (ERA) will decide soon whether it will continue digging here.

There is a chance it will choose not to, which will bring down the curtain

on perhaps nation's most controversial mine, Ranger.

Built on the faultlines of environmental and indigenous land rights policy,

Ranger is at a defining moment. It has provided fuel to nuclear power

stations of the world but the end of its working life is in doubt.

Depressed commodity prices, revived environmental concerns and tightening

purse strings have made the decision over a new mining development at

Ranger a close call.

Having reluctantly accepted mining on their ancestral lands, the indigenous

people who live beside the nation's biggest uranium mine could soon watch

their industrial interloper depart.

Whether life will be better when the mine goes is far from clear.

The town of Jabiru was built quickly to support the mine.

The end of mining at Ranger would be cause for celebration for some.

Environmentalists have long despaired at a mine so close to one of the

nation's most famous national parks.

The fact Ranger produces uranium - the radioactive nature of which can be

dangerous in certain circumstances - has only turbo-charged the opposition.

"The exploitation of uranium within the World Heritage property of Kakadu

National Park, effectively against the current wishes of significant

traditional owners and others, is a historical aberration and ought to

finish as soon as possible," former environment minister Peter Garrett said.

Mr Garrett was minister when ERA was granted permission to conduct further

exploration at Ranger. His decision was constrained to ruling on matters

relevant to a certain environmental act.

The process for environmental approvals for the development of the mine is

ongoing under a new government but Garrett said Ranger had been a blot on

the landscape since day one.

Most affected over the past 37 years have been the indigenous Mirarr

people, whose traditional lands have hosted the mine.

As late as the 1970s, the Mirarr people lived in these monsoonal wetlands,

with little intrusion from white Australian culture.

"There weren't many white people out here permanently before 1980,

something like six or so across the whole region," said Justin O'Brien, the

chief executive of the Mirarr's modern corporate organisation, the

Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation.

The town of Jabiru was built quickly to support the mine and within one

year the Mirarr had become a racial minority.

A sealed road connection to Darwin came only in 1974, and the first stage

of Kakadu National Park was not declared until 1979, in what many viewed as

a political compromise to offset the nationwide controversy over uranium

mining in the region.

With an ancient culture that places special importance on the land, the

construction of several huge mining pits was distressing for the Mirarr

people.

The fact that a 1977 act of Parliament allowed mining to go ahead on Mirarr

lands without their express consent - despite the same act giving a right

of veto to most of the nation's other indigenous groups - only entrenched

the feeling of dispossession and resistance to the mine.

"There hasn't been a great history of fairness or equity here. Mining was

imposed upon people and it marginalised people," Mr O'Brien said.

But over time the Mirarr have scored some important wins, which have

improved the relationship with mining to a degree.

ERA's desire to mine a sacred site close to Ranger called Jabiluka was

largely put to bed in 2005, after a decade of campaigning that resulted in

thousands travelling to Kakadu to create an anti-mining blockade, which

resulted in hundreds of arrests.

ERA has promised not to mine Jabiluka unless the Mirarr give their consent.

There was also the signing of a revised agreement for Ranger last year,

ensuring greater royalty flows to the Mirarr and creating a system for

back-payments.

Royalties for Mirrar, calculated on revenue from annual production at

Ranger, tally about $49 million over the past four years.

ERA estimates it has paid $62.7 million to indigenous groups over the same

period, on top of the royalties paid to federal and territory governments.

Mr O'Brien said the relationship between the Mirarr and ERA, while always

cautious, was better now than in the past.

"Coming off a hell of a low base, the relationship with them is pretty good

at the moment compared to other times," he said.

While acknowledging the pain of the early years, some of the mining

industry's more considered minds privately ponder whether, now the egg is

scambled, the Mirarr will truly be better off if ERA decides to end mining

at Ranger in the next few months.

The mine dominates the local economy. ACIL Tasman judges ERA to be the

source of 87 per cent of Jabiru's regional gross value added activity in

2012, as well as leasing 66 per cent of private dwellings in the town. More

than a third of local school students were children of mine workers.

Malcolm Fraser, the prime minister who controversially approved mining at

Ranger in 1977, said he had no regrets.

"I think there has been a benefit. It was always intended to be of benefit

to the Aboriginal people," he said this week.

The traditional owners' representatives in 1977, the Northern Land Council,

did eventually agree to mining going ahead, he added.

Mr Garrett was less convinced.

"Whilst there has been income flowing through to certain parties, on

balance it has not been a positive for the traditional communities," he

said.

The Mirrar might be asked soon to approve a mine extension at Ranger. ERA

has spent the past three years evaluating a new undergound mine that would

operate until 2021, when the licence expires. If it wanted a new licence it

would have to apply for one.

Mr O'Brien said it was too early to say if Mirarr elders would give their

consent should ERA decided the underground project was viable.

ERA estimates the extension project, known as the Ranger 3 Deeps, would

deliver $10 million to $30 million in annual royalty flows to the Mirarr if

approved, but Mr O'Brien said the Mirarr's decision would not be based on

money.

"You don't see much naked self interest here. When you ask some of the

older women about the big financial implications of their decisions,

particularly Jabiluka, which is ruled out by young and old, they say 'don't

worry, none of that was here before'," he said.

"People might say 'how can a small clan of Aboriginal people who have

benefited from mining even think twice about it?' Well, because they live

downstream and below the bloody thing.

"You have hundreds of incidents, leaks and spills. It is with all that in

mind that the Mirarr consider the current proposal at Ranger 3 Deeps."

A precedent for refusing the cash exists nearby. Traditional owner of

Koongarra, Jeffery Lee, turned his back on millions of dollars worth of

royalties from French uranium miner Areva. Instead he had his land absorbed

into the national park.

Nor would the Mirarr be short of a dime if the royalty flows ceased.

During Mr O'Brien's tenure the Mirarr's money has been invested in an array

of stocks, bonds and financial instruments, with millions put under the

management of firms like Morgan Stanley and Sydney's Harper Bernays.

The portfolio includes a stake in the 15-story Scarborough House building

in Canberra that houses the Federal Health Department.

Mr O'Brien acknowledged that some spending might need to be curtailed if

the royalty flows from mining were to cease. But he said the Mirarr could

still look after their families and fund the odd social program.

Some in the mining industry believe younger generations of Mirarr will

prove more open to mining than the current elders.

Mr O'Brien insisted the Mirarr remained united.

"There will be one view," he said.

"Those elders rarely make a major call on anything without everyone being

present."

About 12 per cent of ERA's workforce are indigenous, and while it would be

happy to employ Mirarr people, no Mirarr people work for the company.

As fate would have it, ERA could barely have picked a worse time to

evaluate a new uranium development.

Prices for uranium have been depressed since an earthquake and tsunami

sparked a nuclear crisis in Japan in 2011.

Most Australian uranium miners haven't made a profit since. ERA has

received just $US46 ($54) a pound for its product during most of this year.

That is 12 per cent below the price it received in 2009.

Commodity prices are not the only threat to the project going ahead. A

series of events over the past year have shaken investors' confidence.

A tank failure in December last year spewed toxic substances around the

Ranger site and prompted a six-month shutdown. Despite official surveys

suggesting none of the substances escaped into Kakadu, a fierce debate

ensued over the mine's social licence to operate in such a delicate and

difficult location.

The exploration results for the project have also fuelled concerns, with

some analysts expressing alarm at the quality of some sections of the

underground geology and cases of unstable rock formations.

At the same time ERA's 68 per cent shareholder, Rio Tinto, is aggressively

cutting back capital spending on new projects.

With Rio focused on boosting dividends rather than building large numbers

of new mines, many doubt it will be willing to spend the hundreds of

millions of dollars that would be required to go ahead with a new

underground mine at Ranger.

When the geological concerns were reported to the market in July, Credit

Suisse published the most pessimistic research note on the project to date.

"We believe the results of the Deeps resource drilling are poor," the note

said.

"Ranger Deeps either adds value or there is close to none, and risks are

increasing towards the latter. If ERA announces at the end of this year

that Ranger Deeps is not viable, then the share price should collapse to

very low levels."

The geological results have been better since then, with the amount of

uranium in the Deeps estimated now to be 6 per cent higher than thought

previously.

Credit Suisse no longer covers the company. Among those that do, most

analysts say the project's chances are finely balanced.

"If uranium prices can hold above $US40 per pound, then the project

potentially looks more viable than it has done for much of the past year.

But the project may yet require higher prices still," Bank of Montreal

analyst Edward Sterck said.

JP Morgan analysts said the weak uranium prices, combined with the 2021

expiry of the mining lease, put ERA in a difficult position.

"We believe the project likely needs prices of $US50 per pound to $US60 per

pound over the life of the project," they wrote.

RBC Capital Markets noted recently the underground project comprised 99 per

cent of ERA's share price value, meaning the ultimate decision would have a

very "binary" impact on the stock price.

RBC analyst Chris Drew said he thought the project was probably viable but

continued weakness in the uranium price could limit enthusiasm for it.

"It is going to depend a lot on the uranium market. The main thing is the

resource looks consistent with what they were expecting. You've also got

some good grades there as well, so it would support an economic operation

based on our relatively conservative uranium price forecasts," he said.

ERA chief Andrea Sutton said the geological results had been consistent

with expectations, and sufficiently good for the company to conduct less

drilling than planned.

The spot uranium price enjoyed a small surge in early November, and while

the longevity of that rise is unclear, Sutton said the company was

confident the price would rebound in the medium term.

"You look at the challenges of climate change, Japan's power needs and the

construction in China, and we do still see that medium term (uranium

demand) strengthening," she said.

While some remote communities face poverty and unemployment when a local

mine shuts, the Mirarr are confident they can thrive in the modern economy

when mining eventually does leave town.

With Kakadu on their doorstep, tourism is already an established industry,

and the Mirarr run a handful of small businesses in the region focused on

the tourist dollar.

One Kakadu highlight tourists do spend money on are the hearty barramundi

fillets Peter Wilson serves at Kakadu Lodge.

Cooked in the pan and served with a melting knob of herb butter, the

barramundi is one of the reasons Mr Wilson's outdoor bar and bistro won a

Gold Plate at this month's Territory dining awards.

But despite his apparent success, Wilson said tourism in Kakadu was getting

harder.

Visitors to Kakadu have been sliding since 2000 and the demographics that

do visit are often not the highest yielding.

"Last year was the worst year for tourism ever that I can remember. This

year is marginally better, but it would need to be," he said.

He is convinced the Jabiru region cannot survive on tourism alone.

"In this region you have a 100-day season. You have 100 days of viable

occupancy that is profitable, then you've got maybe 100 days of break-even

occupancy and then you have got 160 days of pouring money down the toilet,"

he said.

"It needs diversification. For the town to thrive it needs commercial input

into it, people who want to be service providers and have businesses not

just based on tourism.

"The big challenge for Jabiru is what it wants as its focus after ERA, and

that is very much my focus too."

Uncertainty over the longevity of ERA is not the only thing undermining

investment in the town. Jabiru exists under a similar lease to the one the

mine operates under, meaning no business has certainty of tenure beyond

2021.

"Why would any business person invest in infrastructure when they know

there is uncertainty about what is going to happen," Mr Wilson said.

Without fresh investment in facilities, the decline in tourist numbers

could be hard to turn around, he said.

"At the moment we are just going through the motions."

Mr O'Brien stressed that tourism wasn't the Mirarr's only option beyond

mining, with land management also a big opportunity.

Investigations into carbon farming in Kakadu suggest 35 to 50 jobs could be

created in that industry, while the Mirarr are also optimistic about the

trend for indigenous rangers to be spread through the national park in

land-caring and maintenance roles.

"There are many social co-benefits that come with that sort of work in

terms of working on country and they are long articulated," Mr O'Brien said.

Should the economic and regulatory hurdles be cleared there is one last

uncertainty surrounding the Ranger Deeps project that could yet become an

issue.

ERA and the Mirarr appear to disagree over whose will would prevail under a

scenario where the company wanted to proceed but the Mirarr did not.

Mr Sutton said ERA would work closely with the Mirarr to help them

understand the full impact of the project, and the company hoped to win

their support.

But when asked if ERA legally required permission from the Mirarr to

conduct the extension, the company indicated it did not.

"ERA has an authority to mine and produce uranium oxide at the Ranger

Project Area until January 2021," ERA said in a statement.

Mr O'Brien had a different view.

"I would say that in this day and age, particularly given the ignominious

history of conflict here, that is a requirement," he said.

When asked if that requirement was stated explicitly by law, Mr O'Brien

said: "You could argue that it is, and you could argue that it is not."

Perhaps there's one last battle to be fought over Australia's most

contentious mine.

Yellow cake road

*1969: *Ranger ore bodies discovered

*1977: *Federal parliament grants right to mine at Ranger

*1980: *Mining begins

*1981: *First drum of uranium produced

*1994: *Mining complete in Pit 1

*1996: *Mining approved in Pit 3

*1997: *Mining of Pit 3 begins

*1998: *Large protest sees hundreds arrested

*2009: *Discovery of 3 Deeps underground resource announced.

*2011: *Fukushima disaster sends uranium price diving

*2012: *Mining complete in Pit 3

*2013: *New agreement with local indigenous groups

Federal government declares fresh environmental assessment required

Tank failure results in toxic leak

*2014: *Draft environmental impact statement submitted to government.

*2015: *Target for start of mining at 3 Deeps

*2021: *Right to mine expires

Read more:

http://www.smh.com.au/business/mining-and-resources/uranium-mining-in-ka...

Other nuclear news

New Mexico nuclear waste accident a 'horrific comedy of errors'

The curious case of the missing French nukes

Radioactive meltdown a total beat-up

US A10 gunships armed with depleted uranium join fight against ISIS

Miners ask court to lift ban on uranium mining near Grand Canyon

Uranium mining. Unveiling the impacts of the nuclear industry