Shame job Australia – “They came through the gate with my boy’s body more than six hours later” by Gerry Georgatos “They took my boy’s body away. I wanted to go with my son. They left us behind. They didn’t care to listen.” “They just looked at us. They flew off, right in our faces.” “They left us behind.” “They just left us,” said mother, Gwen Sturt.

Through the night, with torrid rains pelting the roof of a remote community home, a family grieved at the loss of a son, a grandson, a brother, a boyfriend, an uncle. The 24 year old Troy Carter dragged his 20 year old brother’s body out of a creek. Six hours later his body would be cared for by his family for the subsequent 18 hours – by the mother and grandmother. Though the young man had passed away long before any chance of saving him, his family shone lights on him all night long.

“They wanted to keep him warm,” said an uncle, Cameron Sturt.

But all night long, Troy’s six year old son, Robert, asked again and again, “What’s wrong with uncle?”

“Why is uncle like that?”

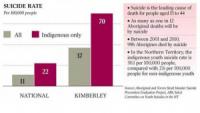

The Kimberley has the nation’s highest Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander suicide rate. It has one of the world’s highest suicide rates. I do not have to belabour the statistical narratives, we all know them.

Last year will sadly return the reporting of an increase in suicides in the Kimberley after an assumed decline in the last few years following a horrific spate of suicides from 2005 to 2008.

The Kimberley has a total population close to 45,000 of which Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander peoples comprise nearly 20,000 residents. However the Kimberley is a tale of two peoples – of Black and White. It is a tale of racialism and racism. The significations should never be underplayed and most certainly should never be denied. The affluent tourist mecca Kimberley divides its social wealth. If you are non-Aboriginal you are more than likely to be doing quite well but if you are an Aboriginal person you are certainly more than likely to be doing it very tough. In part, because of the disparities, social inequalities and inequities there are consequent racialised tensions. Symptomatic of the tensions are the wash of racialised and racist stereotypes to justify various privilege, to justify the deplorable neglect and to justify the great divide between the concomitant racialisation. But in the end we are all one race, just people, and Governments and the national consciousness have to start understanding this.

It is has been advised that researchers and journalists should not publish how someone may have taken their life as it may lead to a contagion effect – ‘copycat’ suicides. I do not agree. Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander communities may not know why one of their loved ones took their life but they always know how – and without exception everyone knows whether it is published or not. In fact, nearly 100 per cent of Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander suicides are by some form of hanging. We should not be concerned as much about reducing the means for one to take their life as opposed to how concerned and focused we should be about reducing the will to do so. Without truth in its raw ordeal we often go backwards while sometimes the only forward steps are small ones. In the majority of prisons evident hanging points have been removed but if someone wants to take their life the means are always innovated, tragically.

In one Arnhem community, out of a sense of having to do something, all the rope was confiscated.

At about 4:30pm on the first Monday in the bloom of the new year, the 20 year old young man apparently suicided by hanging himself from a tree. The family had left Halls Creek for Wunga; for several days downtime on a bush block they owned at the community, 70 kilometres from Halls Creek. The monsoonal rains came in and soon flooded all the roads leading out of Wunga. An hour before apparently hanging himself, the young man had left the household for a walk. A little later his girlfriend went looking for him.

She found him more than a kilometre away hanging from a tree branch near a creek. She rushed back to the house screaming.

According to the uncle – Cameron – the family phoned the police.

“The police told them because of the rains they could not get there till the next morning. This was unbelievable. I don’t understand how the chopper couldn’t fly in immediately. The police told them they would be there probably 9am in the morning.”

“The police gave them advice but what good is advice. They needed help immediately. They needed a response.”

A devastated brother and girlfriend went looking for him. Disoriented in the fast approaching dark, and each step at least ankle high in mud, the girlfriend and Troy took more than an hour to find the tree. With the monsoonal weather, it was soon dark.

They found the tree but the branch had broken. His body must have slid into the creek. Troy waded into the creek looking for his brother. In the dark, he found him, bringing him back.

“Troy tried to carry his brother’s body back to the house but he was sinking knee deep in mud. He went back to the house on his own and got a wheelbarrow,” said Cameron.

“He tried to bring his brother back in the wheelbarrow. Can you imagine the grief?”

“But no matter how he manoeuvred the barrow, he got bogged.”

“Distraught, grieving, he ran back to the house.”

“This time a couple of them returned with a mattress.”

“It breaks me to know what they went through. It breaks me for the boy’s mum, for his little nephew, for everyone. It shouldn’t have been this way.”

“They placed his body on the mattress. In the mud, the slush, the rains, they dragged him back,” said Cameron, choking back cries.

Cameron lives in Derby. Once the family had called him from Wunga about what they were going through he was onto the police too to get them to assist immediately.

“It took them more than six hours after finding his body in the water to get him to the house,” said Cameron.

“I was on the phone with Gwen (the mum) during the moments they finally arrived to the house. It was ten minutes past midnight. I’ll never forget her cries, her pain as she said, ‘they are just coming through the gates now’.”

“I have no problem with most people but I don’t understand why the police couldn’t get a chopper in despite rain and all.”

“They kept his body under lights all night. The little fella he was asking all night long ‘what’s wrong with uncle?”

“I didn’t know what else to do but go out there and rescue them. They were also out of food, supplies and diesel. They were trapped by the flooded roads. Power was done and they were powering everything with the generator.”

“My 18 year old son, Ty, and I, we left Derby by four-wheel and we drove for more than eight hours through heavy rains to Halls Creek.”

“The police and rescue services weren’t going in. We couldn’t leave them there. It can’t be this business of blackfellas will be right.”

“Can you imagine this struggle of theirs in the rains, in the mud, in the dark, all alone?”

It is 550 kilometres from Derby to Halls Creek and usually a six hour drive but with the rains and the dark it took much longer.

“The police landed the chopper, a ten minute flight from Halls Creek, at the property. But the girlfriend had gone wandering. The police spent half a day flying around looking for her. Gwen and everyone were at the house with my nephew’s body. When they found her they took her to Halls Creek and then came back.”

“It was about 5pm when they took my nephew’s body. But they didn’t take Gwen with him who wanted to go with her son. They left everyone behind distraught, grieving, at a total loss, and by now they had run out of supplies and food. The family were devastated, shell shocked.”

“They didn’t understand why they weren’t airlifted.”

Gwen said to me that she begged the police to take her with them and to take the family out.

“I begged them, crying that they take us with them. I should have gone with my boy. They just took him. They said that they were under instructions to take out only my boy and his girlfriend.”

“They said the State Emergency Services would send a chopper in soon enough. They flew off right in my face. I was crying and screaming. It was like they were slapping us in the face.”

Cameron said that the police stated they would contact the State Emergency Services to organise a rescue chopper from Kununurra. But the chopper never came.

“They were 24 hours there with the boy’s body, grieving. Can you imagine what it would have been like in that house for all them? And they were left there in that despair? Would this happen if they were White? How can we not ask this question?”

“I called them off a satellite phone and told them despite the flooded roads I would drive the four-wheel as far as I could, to the turnpike 10 kilometres from the property. I told them that they should walk there through the mud and meet me but not to get it wrong because once they left the house they would be out of phone rang.”

“My sister (Jeanette Swan) who lives in Halls Creeks asked her boss for the troop carrier, and he was good and gave it to her to rescue the family. Jeanette followed me and Ty. But you know, to get there we had to drive through the floods. The water was above our bonnets. It was crazy but we had no choice, we couldn’t leave them out there.”

The family walked through the mud for hours and reached the waiting Cameron, Ty and Jeanette.

“The health services should have come out with us to meet them and tend to them immediately but they didn’t.”

I called the personal mobile of Senator Nigel Scullion, Federal Minister for Indigenous Affairs, and asked him to help. Senator Scullion immediately organised for health and ‘standby’ services to attend. They did.

“They were in shock, a mix of distraught and quiet, trauma everywhere,” said Cameron.

“We brought them back to Halls Creeks where the health people took care of their wounds, helped them and others fed them.”

I cannot but beg to ask how all this could be allowed to occur subsequent the apparent suicide. This isn’t the 1920s, where this tale could be contextually imaginable. It is 2015.

The Halls Creek Healing Taskforce stalwart Donna Smith was appalled. Donna spent the whole day by the family’s side after Cameron, Ty and Jeanette brought them to Halls Creek.

“Gerry, I am devastated for them. You know, if there is a flood, a bushfire, a natural disaster with White communities, rightly so there are huge public, media and Government responses. The army gets called in. All the services respond immediately and there is even sometimes international support because of the blanket media coverage. People get rescued from whatever conditions. Donation appeals go out and donations flood in. But when it’s Black families in trouble where is the response?”

“Things have to change or more of our people will suffer needlessly, continue to live racism, die prematurely. It should not have taken a phone call from you to the Minister to get a response. Response and resources should occur without delay. What are we? Do we not count?”

“We have begged for support for our people in this part of the country. Our people need real hope. Right now they have not got it, so how then can there be healing when there is no hope? We have begged for the Healing Taskforce to be properly funded and now you see for yourself the deaf ears we fall on,” said Ms Smith.

“What will that little six year old boy think as he grows up?”

The family was staunchly supported by Kija State parliamentarian, Josie Farrer, who herself has lost a grandchild to suicide and who hails from Halls Creek. The relentless advocate of her people, and of humanity, Ms Farrer, cried as we spoke at length about what had occurred.

“What this family went through in one way or another many of our families go through. They are treated different, forgotten. It is still a Black and White divide. You and I know both know this. I cannot believe it each times something like this happens even though it happens in one way or another again and again.”

“How much pain must our people endure?”

“Our people are treated as less.”

“This family has lost a son, a grandson, a brother and on top of this devastating grief they are shattered with more pain.”

“The police and the emergency services do have to explain why they didn’t respond immediately. The police should explain why they didn’t take the family out of Wunga.

“It should not have come down to Cameron and his son driving through the night from Derby to rescue everyone.”

“And what to from here? You know there’s no such thing really as standby services and grief support. When I lost my grandchild, there was no support for the family from any service. These standby services are a myth. We are just forgotten.”

The suicides crises hurting this nation have their fundamentals but nevertheless demographically, geopolitically, psychosocially and ‘racially’ different. I am exhausted by the statistics and reasons. I have just completed the draft of a book on the crises. I hope the book makes some sort of difference, opens a few more eyes but in the end no book or report will change the world. Governments must respond, just as the national media is beginning to respond. Suicides are born of a sense of failure or of a sense of hopelessness, or from a sense of oppression. The majority of sucides have poverty as a factor and far too many have racial stressors. Many are the by-product of racism – and this assertion seems to piss off far too many every time I argue it. The hostile denials and selfish justifications are killing people.

In these last two years I have cried many nights as I have worked relentlessly to get Governments to respond to the suicide crises. My loving wife catching me out once in a while staring at walls, or in tears. I must write, that as I cried deeply for Philinka Powdrill of whom I wrote about recently so too did I cry again for Cody Carter and his family – for his 60 year old grandmother, Sandra Sturt, for his 39 year old mother Gwen Sturt, for his 24 year old brother Troy Carter, for his six year old nephew, Robert Carter, for his girlfriend, and I cried for Cameron Sturt, Ty Sturt, Donna Smith and Josie Farrer.

- Declaration of impartiality conflict of interest: The author of this article, Gerry Georgatos, is a senior researcher and community consultant with the Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander Suicide Prevention Evaluation Project (ATSISPEP).

Lifeline – 13 11 14 www.lifeline.org.au

Suicide Call Back Service -1300 659 467

www.suicidecallbackservice.org.au

Kids Helpline – 1800 55 1800 www.kidshelp.com.au

MensLine Australia – 1300 78 99 78 www.mensline.org.au